We are individually and collectively amassing technical debt

We see now that the abyss of history is deep enough to hold us all. We are aware that a civilization has the same fragility as a life.

- Crisis of the Mind, Paul Valery

From Jodorowsky’s Panic Fables

We are all amassing personal and collective technical debt1.

Technical debt is what happens when a pattern is established that is adaptive for one situation, but where the world has changed, and the pattern is no longer adaptive. We build up technical debt by refusing to change the underlying pattern and instead adding a layer of complexity, an additional pattern on top of the old pattern to account for the world change.

There are lots of examples of technical debt in programming (e.g. copy-pasting lightly modified functions, or using magic numbers). One more accessible analogy is building a shelter.

Say you decide one day to build a small guest house on an open field. You lay a simple foundation and build the walls and roof to enclose the space quickly. This design works fine throughout the warm summer months. But as winter approaches, you realize the guest house has gaps in the walls, letting in cold air.

You could tear down the walls, and reconstruct it to include space for insulation material, but the cold wind is blowing right now and you’re already behind on rotating the cows to the new pasture. So for now you hammer in a plank with a bit of spare plastic, blocking the gaps you initially noticed.

Come winter time, the snow comes and now even though the wind is blocked, the cold is radiating through the walls. Cursing, you hammer in wood with the spare piece of cloth, but it does little. The water seeps through the holes and freezes. All there is to do now is shiver until the spring comes.2,3

As the weather cools, it makes sense to add a layer of plastic and wood — a patch for the system. In immediately stops the wind from blowing into the house. But in the context of a snowy winter that is coming, it serves as technical debt: a pattern (in this case a literal pattern of material) that is helps us in the short term, but is unhelpful in the longer term. To more wholly adapt to the winter, we will need to tear down each added layer and construct a wholly new wall.

(Note: I haven’t found a metaphor that stands alone powerfully enough to capture what I’m talking about, so I will use a few different metaphors in this essay).

I’m going to argue that we, in our personal lives and collectively as a society, are amassing large amounts of technical debt in a similar way. By failing to recognize that our patterns are no longer adaptive, we become encaged, stuck, sclerotic.

Personal Technical Debt: Trauma

Maladaptive attachment patterns are one clear example of technical debt and our self system. We might point to trauma as a fairly blatant example:

- After a dog attack during childhood, adults often continue to continue to fear and avoid dogs

- After returning from war, refugees and veterans may freeze in serious shock after the sound of a firecracker

In both cases, the fear response may have been helpful at the time (providing the immediate energy to react) but now actively hinders daily functioning. I want to suggest that this happens at increasingly subtle levels too.

Consider the following example, inspired from a book on attachment therapy4.

Mike, 47, has spent the last six months with someone that he feels is not his intellectual equal. He says he loves her very much, but there’s always an underlying dissatisfaction in Mike’s mind about the relationship. He has a lingering feeling that something is missing and that someone better is just around the corner.

After some conversation with Mike, it was revealed that this has been a pattern of behavior throughout his life. After a few months of healthy romantic connection, Mike would have a sense of discomfort and end up pushing away his partner, in search of something else.

When we turned to the subject of his parental relationship, a cause became more readily apparent. Mike told me that his earliest memory was with his aunt, rather than his emotionally distant and infrequently available mother. After some careful discussion, he opened up and offered that a core memory he had was as a four-year-old, crying outside his mother’s door. He had hurt his knee and turned towards his mother. Hearing his cry and seeing little Mike grasping for her, she had turned away and shut the door behind herself.

Through the lens of attachment theory, we might say that Mike learned early on that turning towards means being punished. To avoid the horror of deep rejection, Mike internalized the pattern of avoiding real intimacy. We might say that early on, his mother’s rejection added technical debt to Mike.

I like the analogy of a tangled knot. Pull on the knot, and the rope will move at the beginning. Keep applying more force, and you get less and less out of the knot until it’s so tight that unraveling it seems impossible. Each tug is a layer of technical debt. Each tug makes it harder to unravel the rope.

Framed in this way, it becomes clear that de-layering cannot be done by adding more force, or adding another patch. We may instead have to add more slack, or pull on a different part, to begin to untangle.

We are often taught that our financial insecurity or social anxiety is something ‘wrong with us’. Seeing it instead as a maladaptive pattern can be empowering.

Collective Technical Debt: Institutional Stagnation

From Joseph Tainter’s The Collapse of Complex Societies:

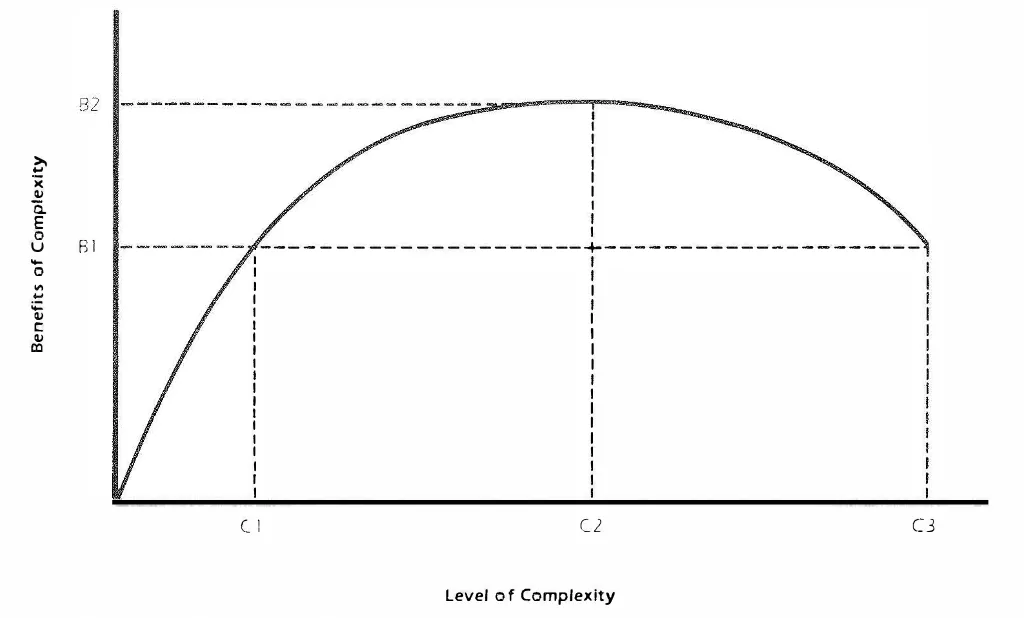

At the beginning of this chapter it was proposed that four concepts would lead to an understanding’ of collapse. These are:

- human societies are problem-solving organizations;

- sociopolitical systems require energy for their maintenance;

- increased complexity carries with it increased costs per capita; and

- investment in sociopolitical complexity as a problem-solving response often reaches a point of declining marginal returns.

To reinterpret Tainter in the lens of technical debt: societies initially establish adaptive patterns to respond to real problems. In response to a growing population, a society will invest in more intensive planting and harvesting. In the beginning, the increased agricultural productivity will allow more and more people to live in proximity. At some point, however, the nutrients in the soil are depleted, weeds outcompete the concentrated grain crops, and a savanna forms. The pattern of behavior doesn’t adapt to the changing world. This is what happened with the Mayans in the Southern Lowland. There are similar stories to tell about the Hohokam in the American Southwest, the Egyption Old Kingdom, and the Harappan in the Indus Valley5.

Some contemporary examples of technical debt:

- When the modern income tax was originally established by the 1913 Revenue Act, the total page count was around 30 pages. As of 2022, the U.S. tax code, including regulations and IRS rulings, is over 74,000 pages. No one person fully understands the tax code. Companies can now, for instance, reincorporate in another country with lower tax to minimize total taxes.

- The bloated defense contractor ecosystem in the U.S. military-industrial complex:

- The F-35 fighter jet is an excellent case study. Lockheed Martin, the prime contractor, subcontracted over 1,500 domestic and foreign companies. Initial cost estimates of $233 billion ballooned to over $400 billion after the aircraft was over a decade behind schedule.

- Mid-2020, the online employment portals of Kansas, New Jersey, and Connecticut were down as six million Americans filed for unemployment benefits. It was because they were written in COBOL, an old and notoriously verbose programming language.

The problem with technical debt

The problem with accumulating technical debt is that it takes more and more energy to remain functional. Forcing yourself to remain focused on debugging a segmentation fault takes after you spent the past week staying up writing investor memos takes more energy than you may have. So does hiring a team of accountants to file your taxes. Eventually the energy demands are too great and the system collapses.

It is impossible to create a perfectly flexible set of patterns that will always be adaptive. A pattern requires a frame, but the world doesn’t stay still. There is no perfect plan6. What we are left with is movement.

Thanks to Jake Orthwein for giving feedback on this essay.

Postscript:

I am not totally satisfied with my analysis here. There are two more subtle phenomena I mean by ‘technical debt’ I want to articulate: one is about ‘additional work required’ (that gets captured in the house wind metaphor) and another is about ‘valley hopping’ where “things look like they get worse before they get better” (as with the knot metaphor). I haven’t figured out how to relate these to social technical debt. I’d also like to figure out how Taleb’s notion of antifragility relates to all of this.

You can get regular updates from my substack here.

-

This framing was inspired by Mark Lippman’s introduction in his meditation book: https://meditationbook.page/#technical-debt-meditation-and-minds ↩︎

-

I haven’t found an entirely satisfactory metaphor for personal physical debt. This is good, but is a bit too suggestive of the idea that a solution exists. I don’t mean to imply that a solid ‘solution from the beginning’ exists. The answer isn’t a better plan, but a more fluid capability to respond. ↩︎

-

Unlike the builder who knows that winter is coming, we don’t know what the future is going to demand of us. There is no ‘perfect house plan’ that we can rely on: to adapt, we will need to be able to smoothly decide when it is appropriate to hammer in a layer of wood and plastic, or else to tear down the entire wall. ↩︎

-

Levine, Amir, and Rachel Heller. Attached: the new science of adult attachment and how it can help you find–and keep–love. Penguin, 2010. I heavily modified an example. ↩︎

-

Tainter, Joseph. The collapse of complex societies. Cambridge university press, 1988. pp.46-50 ↩︎

-

For a formal explication, see Chapman, David. “Planning for conjunctive goals.” Artificial intelligence 32.3 (1987): 333-377. ↩︎