Technology is not inevitable

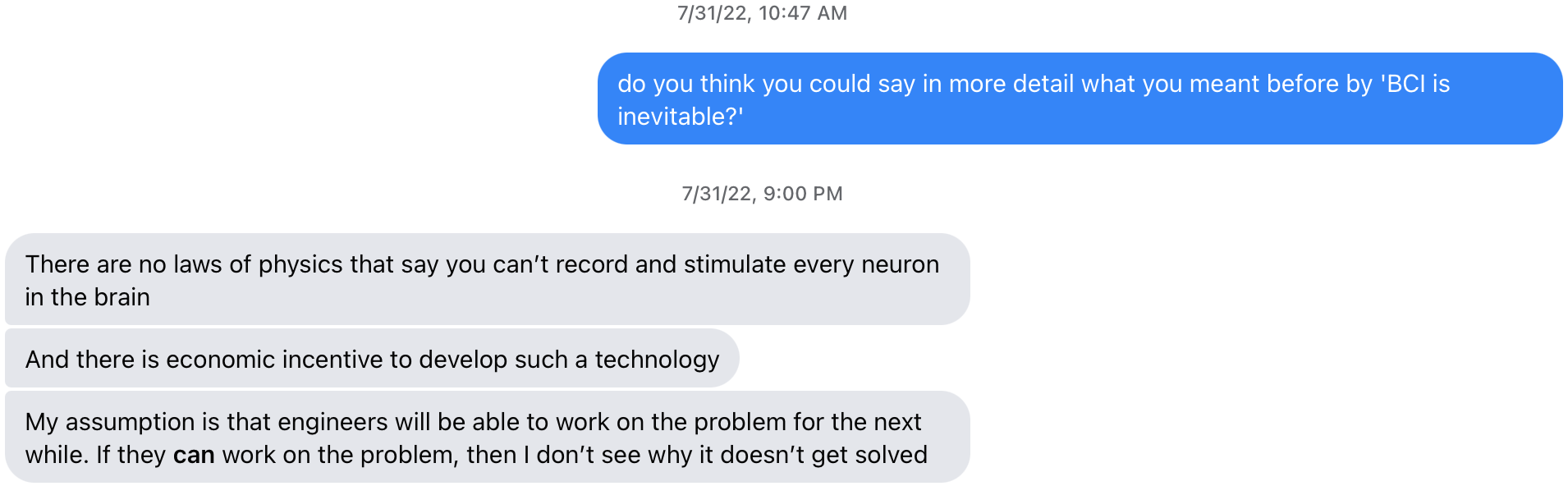

When talking to certain technologist friends about brain-computer interfaces and artificial general intelligence, I’m struck by how often I hear that such idea-complexes1 are referred to as ‘inevitable’.

In this example, my friend (who I’ll use to represent the various people2 who’ve held this stance) basically says: ‘if it is physically possible, and there is economic incentive, it’ll happen’. Let’s put aside the initial question about the ambiguity of what counts as BCI/AGI.

I’m going to argue that claims about technological inevitability are wrong and monopolistic.

Technological feasibility and economic incentives do not imply inevitability

When I say ‘BCI is inevitable’ is wrong, I mean that this is a misleadingly strong prediction about the future. I don’t mean ‘BCI will not happen’. Nor, am I suggesting that the future is inherently nondeterministic.

Here are a few examples of technologies that are both physically possible and economically incentivized yet have either been greatly delayed or outright banned. From Katja Grace’s “Let’s talk about slowing down AI”:

-

Huge amounts of medical research, including really important medical research e.g. The FDAbanned human trials of strep A vaccines from the 70s to the 2000s, in spite of500,000 global deaths every year. A lot of people also died while covid vaccines went through all the proper trials.

-

Nuclear energy

-

Fracking

-

Various genetics things: genetic modification of foods, gene drives, early recombinant DNA researchers famously organized a moratorium and then ongoing research guidelines including prohibition of certain experiments (see theAsilomar Conference)

-

Nuclear, biological, and maybe chemical weapons (or maybe these just aren’t useful)

-

Various human reproductive innovation: cloning of humans, genetic manipulation of humans (a notable example of an economically valuable technology that is to my knowledge barely pursued across different countries, without explicit coordination between those countries, even though it would make those countries more competitive. Someone used CRISPR on babies in China, but wasimprisoned for it.)

-

Recreational drug development

-

Geoengineering…

From the 60s to the 80s, people really believed that nuclear power was the future. As late as 1987, Asimov thought that nuclear fusion would be widespread by 20203. Many were similarly confident about nuclear energy4. Even though nuclear energy made sense technologically and economically, public opinion has turned against it after a series of memorable disasters5, indefinitely stalling progress.

Perhaps a stronger example is genetic modification of humans. Countries could have workshops with human-like clones but genetically modified to align lithography photomasks to more quickly create semiconductors. We don’t see anything close to this because people like Federico Mayor6 helped create consensus around the Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights.

Another thing to note is that economic incentives change over time. In a market economy with strong individual rights, there is a heavy incentive for consumer goods. In an economy heavily managed by the state, incentives shift towards the goal of the state, whether that be stronger military capacity or civil infrastructure. Because economic incentives are not static, we cannot say that it makes a technology inevitable.

Alongside flying cars and subsonic intercontinental travel, human genetic modification remains a specter in the distance. It may eventually happen, but any claims about its inevitability are not well substantiated.

“Technology is inevitable” can be dangerously self-fulfilling

We deform the world according to our expectations. When this happens, we call it a ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’. The world is more deeply filled with self-fulfilling prophecies than we recognize, so we should be very careful about our ‘prophecies’, lest they crowd out visions of the future we want.

Consider stock-market crashes. “Short-sellers” can cause companies to go bankrupt by publicizing a persuasive case for why a particular company should not be valued so highly. If the short-seller is reputable, the stock price will crash within the next few days7. One way of framing this is that the narrative power has shifted from the company (“we at E-corp are an honest and profitable business”) to the short-seller (“E-corp is a pyramid scheme that rests on fraud”). The fundamental economics of the companies remain the same, but the shift in narrative power can convince shareholders to sell and drive the company bankrupt8.

Let’s turn back to AGI. The conception of “AGI” in the narrative that “AGI is inevitable” is part of a fairly specific vision of AI. It evokes paperclip maximizers, agents with utility functions, a monstrous superintelligence. Because its proponents were early and vocal, “AGI” as a frame has monopolized the narrative power. This has crowded out other visions of AI systems that are both technologically feasible and more socially desirable9. Drexler’s ‘Comprehensive AI Services’, for instance, does not involve a power-seeking superintelligent agent10.

The future is less certain than we realize, and a wise course of action involves acknowledging both our uncertainty but also the way that narrative power can shape outcomes. Be wary the oracle bearing the message that their technology is inevitable.

For inspiring and refining this essay, I thank Raffi Hotter, Saffron Huang, Henry Williams, and Helen Toner.

Footnotes

-

I think it makes more sense to refer to BCI/AGI as big parts of an idea machine, to use Nadia Aspourahova’s term, rather than a distinct technology.↩ ↩︎

-

See, for instance, Jeff Clune at ~45:00 in https://twimlai.com/podcast/twimlai/accelerating-intelligence-with-ai-generating-algorithms/↩ ↩︎

-

“nuclear fusion [will] offer a controlled and practical source of unlimited energy”. See “The Elevator Effect” from https://archive.org/stream/66EssaysOnThePastPresentAndFuture/IsaacAsimov-66EssaysOnThePastPresentFuture-barnesNobleInc1993_djvu.txt↩ ↩︎

-

See Karnofsky https://www.cold-takes.com/the-track-record-of-futurists-seems-fine/ and the informative response from Dan Luu https://danluu.com/futurist-predictions/↩ ↩︎

-

Though I haven’t read it, Weart’s ‘The Rise of Nuclear Fear’ is apparently very good on this.↩ ↩︎

-

See https://www.researchgate.net/publication/26402030_The_Significance_of_UNESCO%27s_Universal_Declaration_on_the_Human_Genome_and_Human_Rights↩ ↩︎

-

This happened with Bill Ackman and Herbalife, the pyramid scheme pharmaceutical company. Hindenburg Research’s report on the Adani group caused a $90bn decrease in market value across their companies.↩ ↩︎

-

We don’t realize that this is happening all the time. Hype cycles, the placebo, the ‘pygmalion effect’, stereotypes, predictive policing, the CAPM pricing model#. You might say that every moment, we are collectively sustaining and hallucinating hyperobjects into existence.↩ ↩︎

-

See, for instance, Drexler’s ‘Comprehensive AI Services’ and ‘Open Agencies’, and Audrey Tang’s ‘Digital Pluralism’. Also Eckersley on the analogy between capitalism and gradient descent and Chiang’s metaphor of AI as a corporation.↩ ↩︎

-

There are many debates over whether AI will “really be” an agent or a tool (see e.g. Gwern’s “Why tool AIs want to be agent AIs”), but these discussions miss the self-fulfilling power of narratives.↩ ↩︎